This week two congressional committees -- the House Judiciary Subcommittee on Courts, Intellectual Property, and the Internet and the House Committee on Energy and Commerce -- will hold hearings to examine issues that relate to changes in today’s video entertainment marketplace and to satellite copyright licenses that are set to expire in 2014. And if there is any constant in each of these inquiries, it ought to be a recognition of how significantly and how thoroughly the video marketplace as changed since the Cable Act of 1992.

Indeed, back when the Cable Act was enacted, the video marketplace, its competitors, its technology, and its content were enormously different. For example, back in 1992, there were no non-cable companies amongst the top ten video providers. Today, consumers have more choices that ever before; satellite and telco video providers represent 4 of the top 8 multichannel video providers, and that does not even count new Internet-delivered providers like Netflix that today has more video subscribers that Comcast.

But despite such rapid change, much of the video marketplace still labors under a statute premised on 20 year old assumptions of market power that today ring hollow. Increasingly, courts are joining the chorus of commentators in recognizing that a changing video marketplace can no longer justify reliance on intrusive government regulation of cable operators.

This past May, DC Circuit Judge Brett Kavanaugh highlighted this point quite eloquently in his statement on the Comcast-Tennis Channel case when he noted that "[i]n restricting the editorial discretion of video programming distributors, the FCC cannot continue to implement a regulatory model premised on a 1990s snapshot of the cable market.'"

Echoing this sentiment, a Second Circuit panel last week commented similarly in stating that “[T]here is no denying that the video programming industry is dynamic and that the level of competition has rapidly increased in the last two decades. In light of these changes, some of the Cable Act’s broad prophylactic rules may no longer be justified.”

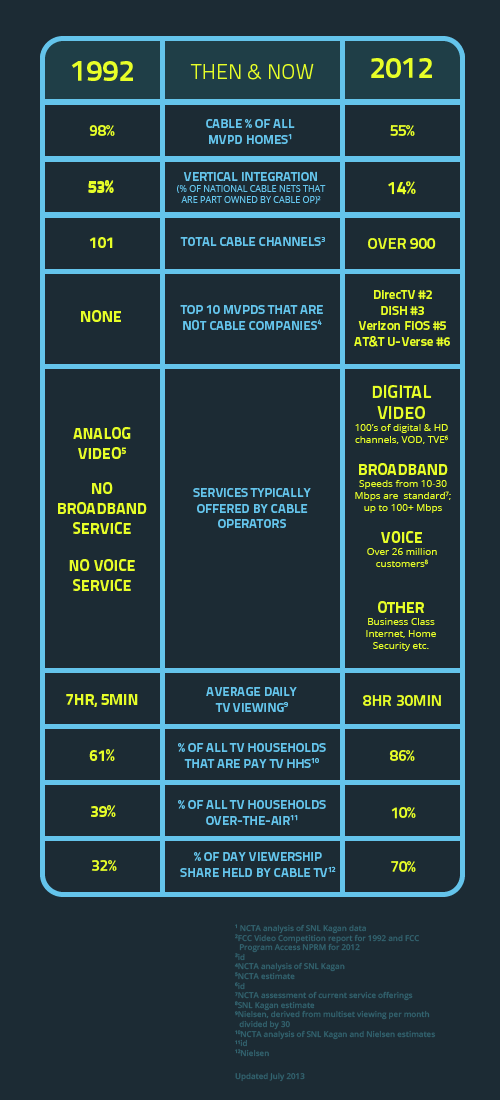

Technology moves so quickly. It can be difficult to see how far and how fast video distribution and technology has changed since the early 1990s. The chart here shows side-by-side some of the key changes that separate today’s video marketplace from yesterdays. It reveals how regulation considering the challenges of the early 1990s may not make sense in 2013. In 1992, cable was essentially the sole provider of video subscriptions, with satellite companies barely in existence. Today, the video marketplace is thriving with competition between cable, satellite, telco and Internet video services all battling for viewers. We’ve gone from barely 100 channels in 1992 to more than 900 today. Twenty years ago, most people watched broadcast channels, while today most spend their TV time watching cable networks. A lot has changed in the video marketplace with consumers having more choices for their video entertainment that ever before.

Given the pace of such consumer driven-innovation, it’s not surprising that many existing legal obligations – particularly those that fall only on cable operators – seem woefully outdated and out-of-touch with marketplace realities. Why force cable customers alone (or anyone for that matter) to bear costs imposed by the FCC’s “integration ban” that limits the development of less costly, more energy efficient set-top solutions? Why saddle cable with “must buy” obligations that force cable operators to sell broadcast channels as part of most cable packages? Against that backdrop, it is entirely appropriate that Congress “pressure test” the current statute so as to promote fair competition and to eliminate those laws and regulations that have outlived their usefulness.