The United Nations reported a plethora of interesting Internet factoids, including the most and least affordable countries for broadband subscriptions.

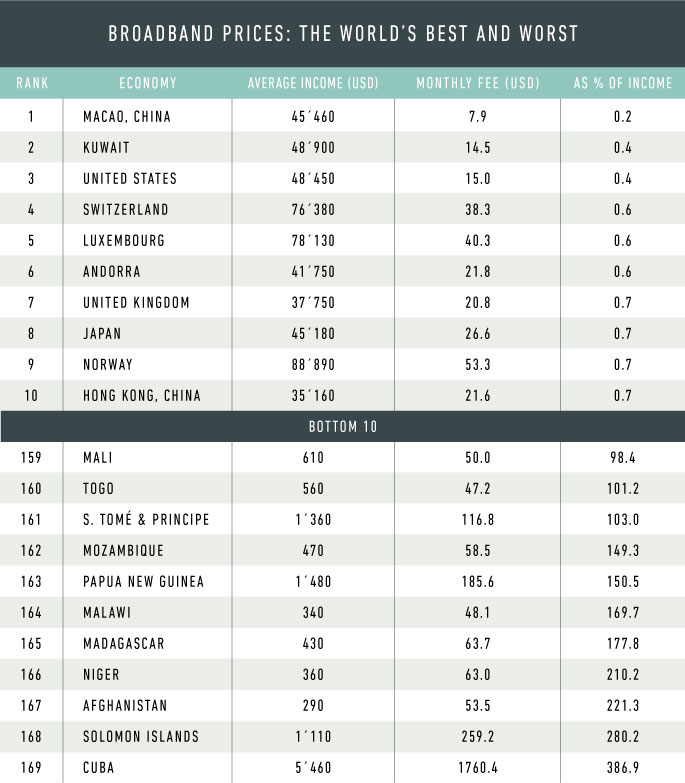

There are parts of the world where even the slowest of Internet connections is incredibly expensive. The cheapest broadband subscription in Cuba costs a wallet-hemorrhaging $1,760 per month, if you can believe that. It works out to be nearly four times the average salary on the island, which earned it last place on the United Nation’s list of broadband affordability. You might ask why the Cubans have to suffer this extortion, and it’s a long story, but it’s largely due to the authoritarian politics of Havana. The UN’s specialized agency for information and communication technologies, the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), released its annual report earlier this month, which charts the state of Internet connectivity across the globe. Along with Cuba’s connection costs, the ITU revealed that over 40 percent of the global population will be online by the end of this year, though that figure is largely bolstered by well-developed economies.

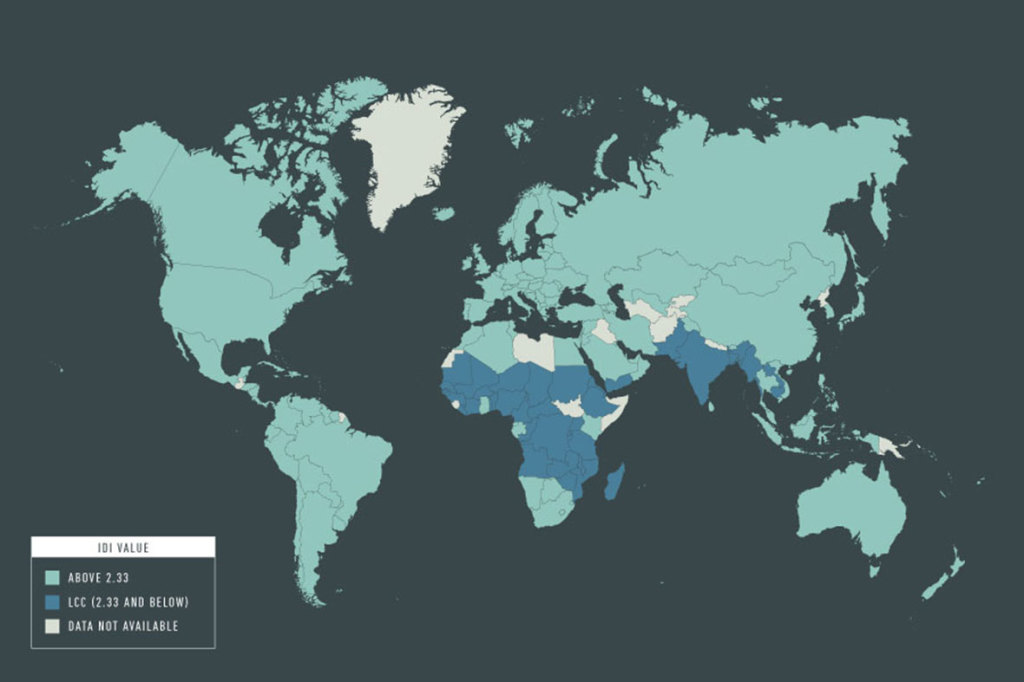

Connectivity in developing countries remains frustratingly low, with as few as one in ten people regularly using the Internet in some parts of the world. With this figure in mind, it seems somewhere between improbable and impossible that the Broadband Commission for Digital Development (an offshoot branch of the ITU) will manage to reach its ambitious goal that at least 60 percent of the world should be online by the end of 2014.

That said; the actual number of people connected to the web might not be the most important metric to look at. Michael Best of the Georgia Institute of Technology, who contributed to the ITU’s study, says we ought to be focusing on a county’s population of digital natives. A digital native is someone who’s spent most of their life connected with technology, typically someone relatively young who was born around the time that personal computers were becoming ubiquitous. A digital native is someone who is inherently comfortable around technology and the Internet. A high percentage of the younger population should be digitally native in a technologically advanced and well-connected country.

“The position of the young is the future, which is defined by technology. The intersection of youth and technology is a driving force,” says Best. Nearly all millennials in the U.S. qualify as digital natives. “The U.S. is up there in the top five or ten of nations with roughly 95 percent,” he added.

It may not be so surprising that wealthy countries like the U.S., Japan, and EU nations have a high number of digitally native millennials – they have the money and infrastructure to get people online in large numbers. But the ITU’s report did divulge some unexpected findings. Malaysia performed much better than expected for a so called “middle income country,” which is “explained by their technology investment in schools,” says Best.

In contrast, “We also see Qatar is performing less well than we would have expected. Even though they have good IT infrastructure,” says Best, and he thinks it may be due to gender inequalities in the Middle Eastern country. “We looked at the ratio of girls to boys in schools. If there are more girls in schools this shows a statistically significant association with digital nativism.”

The distinguishing factor between developing and developed nations wasn’t just the raw number of people online, but also the specific demographics of the people online. In wealthy countries everyone, young and old, is likely to use the Internet on a regular basis, but “there’s a much larger generational gap in the poorer countries,” said Best.

The main barrier that impedes broadband uptake across poorer counties is twofold says Best. It’s partly due to a lack of developed infrastructure, but it’s also boils down to the cost of a connection. The ITU looked at the affordability of broadband in countries across the globe, they measured the cost of an entry-level broadband subscription as a percentage of the average salary in that country.

The top ten and bottom ten countries are shown in the table above. Note that the U.S. chalks up as the world’s third best, behind the comparatively tiny Kuwait and Macau. Cuba, with its exorbitant subscription fees, comes in last, followed at a distance by the remote Solomon Islands.