It’s expected that by 2020, the world will have 50 billion Wi-Fi enabled devices. Everything from baby monitors and tablets to things we can’t even imagine today will be voraciously feeding off of the wireless broadband in our homes, cafes, and even in our public parks. It’s practically ubiquitous now, but the seemingly magical technology that enables Wi-Fi is barely fifteen years old.

When it was first deployed, wireless Local Area Network (LAN) systems were designed to serve a limited number of business applications under controlled environments. Picture a storage facility floor where employees check inventory with a wireless scanner. Today, wireless LANs fuel everything from the biggest billion-dollar businesses to your iPhone.

Today, people are using Wi-Fi on so many devices and for such data-heavy applications that the frequency utilized to transmit Wi-Fi is becoming saturated.

The current standard, 802.11n, has largely operated in the 2.4 GHz band. 802.11n is capable of a theoretical maximum 300 – 450 Mbps per transmission point. This may seem pretty fast, but looking towards the future, it’s not going to be enough. That’s where 802.11ac comes in. It’s capable of 1Gbps and operates in the 5 GHz band, which means it can handle more users, more devices, bigger apps, and pull more of the burden off of cellular networks.

But just as exciting as new super-speeds is the ability of 802.11ac to support multiple devices in open spaces. The older 802.11n was capable of four spatial streams while the new 802.11ac is capable of eight. This means that if 10 people are using 30Mbps on a public 802.11n Wi-Fi system, 20 could use the same amount on the new 802.11ac system, even if the maximum speed of the new system was the same as the old one.

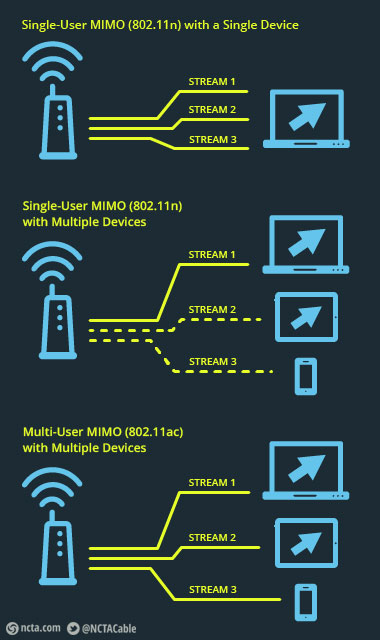

This works because of 802.11ac’s multiple-user multiple-input multiple-output capabilities (thankfully abbreviated as Multi-User MIMO). The old system supported a single-user MIMO per access point, which could only offer full benefit to one device at a time. The new smarter system allows an equal amount of bandwidth to be assigned to multiple users simultaneously. The graphic below shows how Single-User MIMO has to switch “attention” between multiple devices in order to deliver a connection, but Multi-User MIMO can simultaneously connect.

What this all means is that 802.11ac is perfect for outdoor public Wi-Fi applications where many people are accessing the network on a variety of devices. This is particularly exciting for cable because of the already 400,000-plus public Wi-Fi hotspots we’ve installed across the country. They’re available for no extra charge to cable broadband customers and while they’re revolutionizing how broadband is accessed outside the home, they’re also testing the limits of what the old 802.11n can do – especially in densely populated areas like New York City and Washington, DC. In order to keep up with demand, we need to transition to the new 802.11ac standard.

Unfortunately, transitioning to 802.11ac isn’t as easy as installing new hardware. It’s really about two things: (1) providing additional access to the 5GHz band that allows 802.11ac to work to its full potential, and (2) protecting unlicensed spectrum from technologies like LTE-U that are not currently designed to share the band fairly.

This is why it’s imperative that the FCC not only remove barriers to use of the 5 GHz unlicensed band for next generation Wi-Fi, but also make sure that new entrants into the unlicensed bands play by “polite” rules of spectrum sharing. You can learn more about LTE-U and spectrum sharing on a blog we wrote recently.

As a country, we have the opportunity to establish ourselves as a global leader in public Wi-Fi availability, speed, and scale. By both ensuring access to unlicensed spectrum the 5 GHz band and by making sure all users of unlicensed spectrum co-exist politely, we can protect what has quickly become the most utilized (not to mention useful) platform for Internet access.