Right now in the United States, tens of millions of consumers are using the Internet to search for a job, do homework, plan travel, buy shoes and stream live video content. These consumers are accessing the Internet through wired and wireless broadband connections of varying speeds. Over time, the number of people using broadband consistently has increased, as has the speed of the connections they use, regardless of technology. Sounds like good progress, right? Most people would say yes, but apparently the FCC views the situation differently. Later this week the agency is set to issue its annual, congressionally mandated Broadband Progress Report. The report is receiving attention in the press – not because it is the first “annual” report the agency is issuing since 2012, but because the FCC reportedly will change the definition of broadband to a minimum 25 Mbps downstream and 3 Mbps upstream, basically declaring that anything below 25 Mbps is no longer “broadband.”

"Adopting a broadband definition that excludes services relied on by tens of millions of customers...seems like an odd choice."

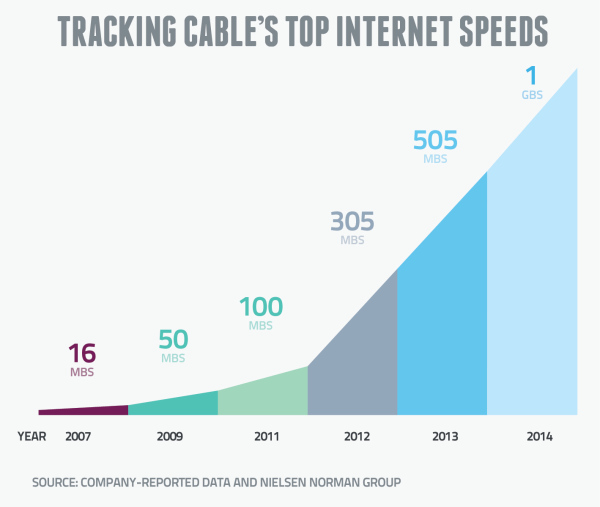

Think about that for a second. The device in your pocket that you can’t stop looking at? Not broadband. The DSL connection that millions use for streaming Netflix? Not broadband. The $10 billion that the FCC is about to offer exclusively to incumbent telephone companies (i.e., DSL providers) for rural service? Not paying for broadband. In the context of a Broadband Progress Report, adopting a broadband definition that excludes services relied on by tens of millions of customers, including services that the agency is subsidizing to the tune of $10 billion, seems like an odd choice. It’s kind of like doing a survey of the automotive business but excluding cars that get less than 50 miles per gallon. Or measuring the performance of middle school students by making them take the SATs. In both cases you may unearth some interesting facts or trends, but neither is a logical way to measure the current state of affairs or the progress that has been made up to the time of the report. Some are suggesting that NCTA is against this definitional change because the cable industry doesn’t want to deliver consumers faster speeds or improved infrastructure. This is laughable. The cable industry was not only the first to introduce residential broadband to American consumers, but we’ve continued to invest billions annually to increase both the speed and capacity of our networks. See the chart below which shows how cable’s broadband speeds have steadily climbed. The idea that we’re opposed to this definitional change because we think 25 Mbps isn’t a worthwhile offering – that we don’t want you to have faster Internet - is truly absurd.  Although you would never know if from much of the press coverage, not only are we delivering 25 Mbps on a broad scale today, we have supported the idea of the FCC reporting broadband deployment and adoption at even higher speeds. As we told the Commission in comments last year, “an approach that tracks baseline service (at least 4 Mbps downstream), as well as two to three higher speed levels (e.g., at least 10 Mbps downstream, at least 100 Mbps downstream, and at least 1 Gbps downstream), would better enable the Commission and the public to understand the current state and future trajectory of the broadband marketplace.” Done correctly, we think there is tremendous value in a periodic report that accurately charts our nation’s progress with respect to broadband deployment and adoption at various speed levels. Such a report allows the FCC and the public can see where progress is being made and where it is not. But unfortunately, the FCC appears to be letting the prospect of new regulatory power cloud its objective assessment of how Americans generally use broadband today, and how our capabilities today compare with those in prior reviews. If the Commission concludes that broadband is not being deployed on a reasonable and timely basis – a virtual certainty if it picks a new 25/3 standard for broadband that only a minority of customers today use – it gains additional authority under the statute. At the end of the day, it’s easy to see how this new standard aids the FCC in expanding its own power, but it’s hard to see how this decision is helpful in accurately evaluating how most Americans use the Internet today. As an industry that is investing billions annually to deliver gigabit speeds, we have every confidence that broadband speeds will continue on their unassailable upward trend, making the pre-determined decision of the Commission all the more discouraging.

Although you would never know if from much of the press coverage, not only are we delivering 25 Mbps on a broad scale today, we have supported the idea of the FCC reporting broadband deployment and adoption at even higher speeds. As we told the Commission in comments last year, “an approach that tracks baseline service (at least 4 Mbps downstream), as well as two to three higher speed levels (e.g., at least 10 Mbps downstream, at least 100 Mbps downstream, and at least 1 Gbps downstream), would better enable the Commission and the public to understand the current state and future trajectory of the broadband marketplace.” Done correctly, we think there is tremendous value in a periodic report that accurately charts our nation’s progress with respect to broadband deployment and adoption at various speed levels. Such a report allows the FCC and the public can see where progress is being made and where it is not. But unfortunately, the FCC appears to be letting the prospect of new regulatory power cloud its objective assessment of how Americans generally use broadband today, and how our capabilities today compare with those in prior reviews. If the Commission concludes that broadband is not being deployed on a reasonable and timely basis – a virtual certainty if it picks a new 25/3 standard for broadband that only a minority of customers today use – it gains additional authority under the statute. At the end of the day, it’s easy to see how this new standard aids the FCC in expanding its own power, but it’s hard to see how this decision is helpful in accurately evaluating how most Americans use the Internet today. As an industry that is investing billions annually to deliver gigabit speeds, we have every confidence that broadband speeds will continue on their unassailable upward trend, making the pre-determined decision of the Commission all the more discouraging.